Smart-from-below

Previous Discovery Next Discovery

The acronym S.M.A.R.T initially referred to the rise of devices that can learn from their own usage. This capacity has become much extended by the rise of algorithms and Artificial Intelligence. But our research showed that this autonomous learning is currently far less important than the ability of users to transform their smartphones after they have been purchased. Once we own a smartphone, we ignore some apps and download others, we change settings, and above all, add our own content. This means that the location of adaptation and development has shifted from professionals to the general public.

In the area of health, for example, we found that the key to understanding how smartphones are used for health was not the bespoke smartphone apps that are being created across the world (often referred to as mHealth). It was the creativity of ordinary people in adapting the apps they were already comfortable with for their own health purposes: this could mean a nurse in Santiago (Chile) using WhatsApp to help a patient navigate a difficult medical system, or a retired civil servant in Yaoundé (Cameroon) using YouTube to get practical advice on making healthy drinks. Although these are all examples of people using smartphones for health purposes, this is not being done through health apps developed by healthcare systems or pharmaceutical companies: this is sometimes referred to as ‘informal mHealth’.

We, therefore, developed a smart-from-below approach to research. This meant that we spent our time observing and collating evidence for how people were already adapting their smartphones for health.

An example of this is Marília Duque’s 150 page manual on using WhatsApp for health, which can be found in the ‘Publications’ section of our website and is based on Duque’s observations in Brazil. In describing the creative ideas for how to use WhatApp for health that she observed in Brazil, the manual illustrates the concept of ‘smart-from-below’: Marília and her research participants (in this case, patients, nurses and healthcare professionals) did not invent WhatsApp, but she used her observations about the app’s use in different health contexts to create a set of best practice ‘protocols’ that could be applied if an organisation did want to trial using the WhatsApp to communicate with patients, for example, thinking about factors like what phone should be used in a particular hospital and how patients could send information about their symptoms to healthcare professionals.

The short film below talks about our approach to mHealth:

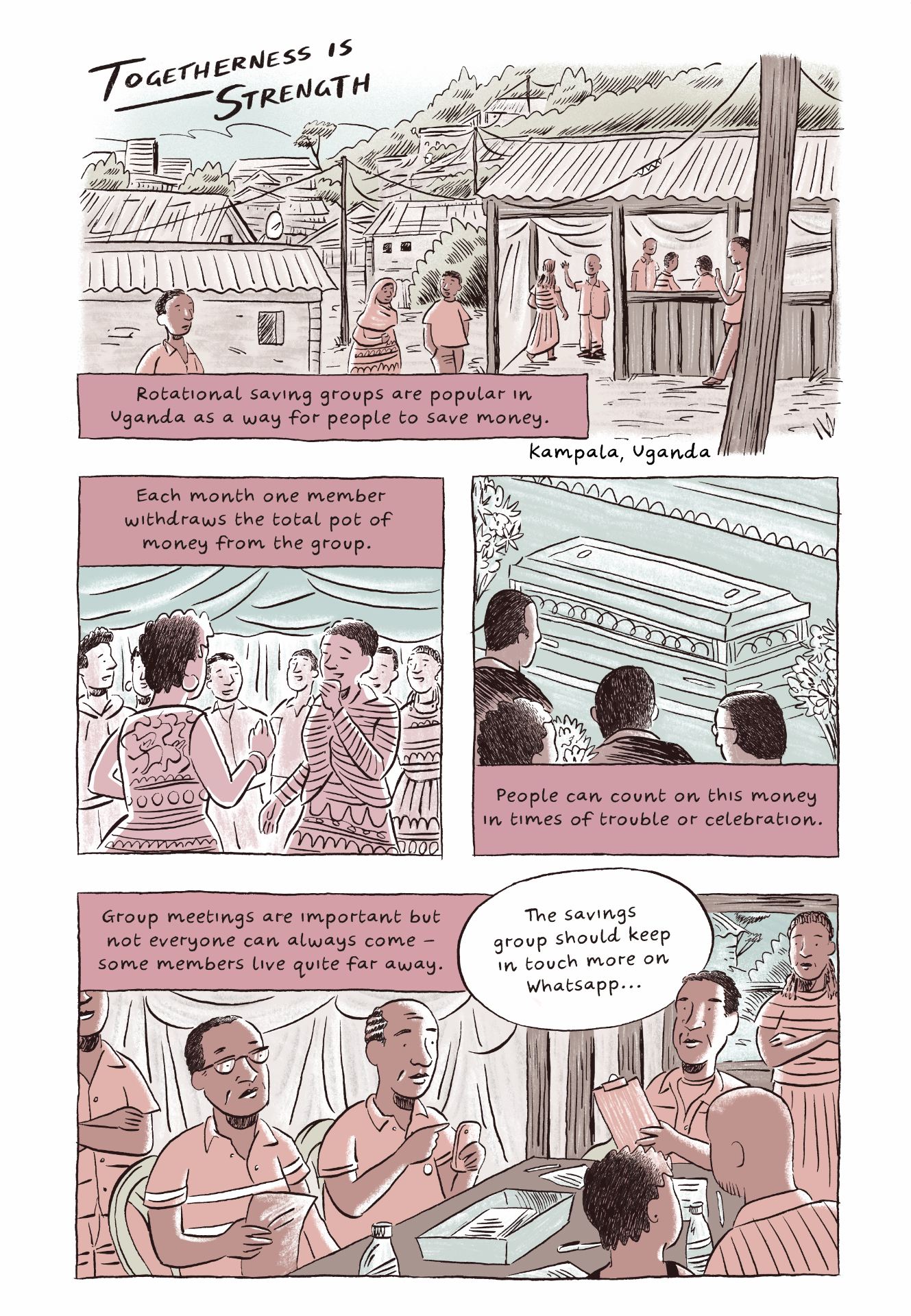

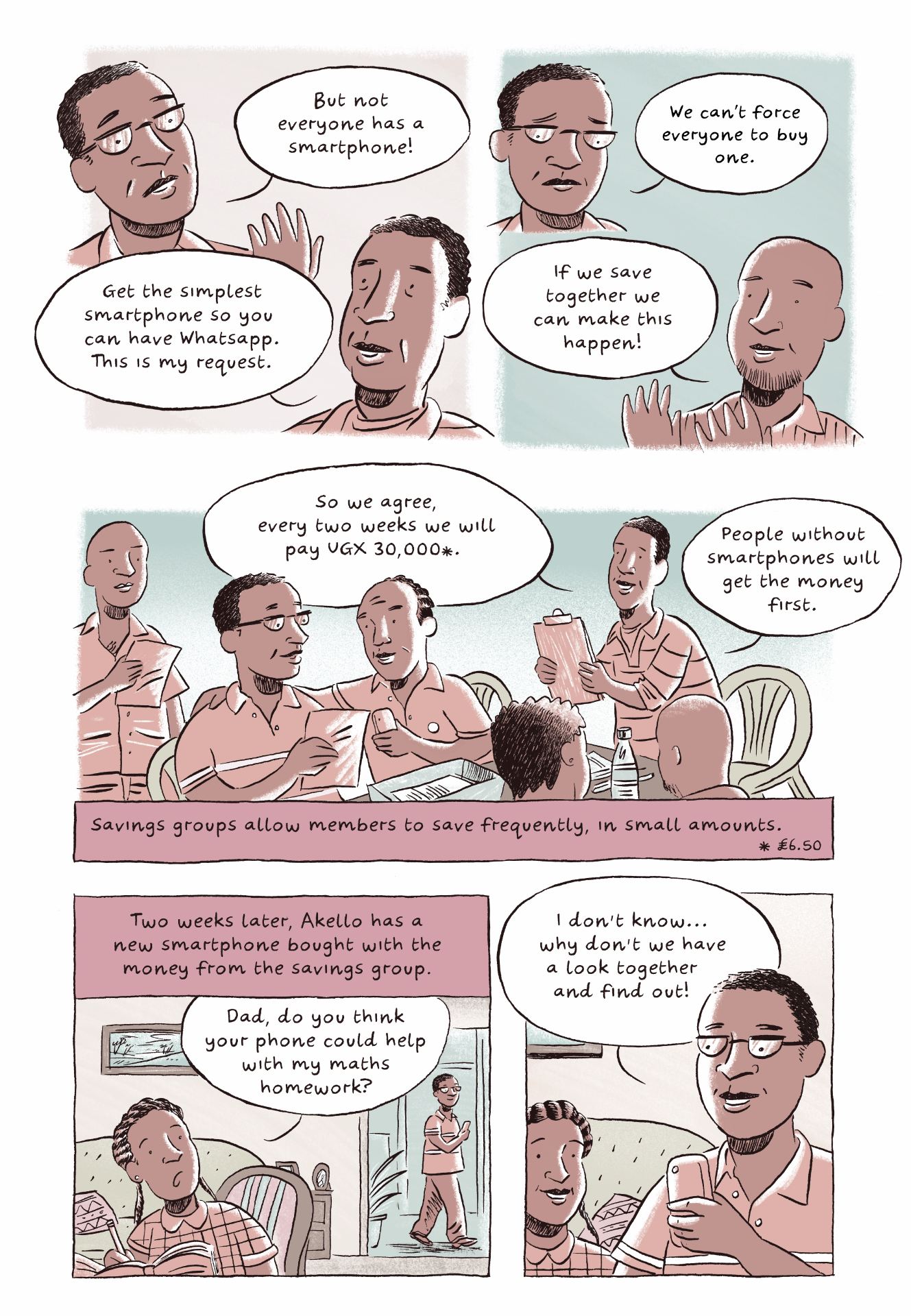

In the following comic, also scripted by Laura Haapio-Kirk and Georgiana Murariu and created by John Cei Douglas, we see how a community comes together to save money for smartphones through a rotation savings group, which is quite common in Kampala. Groups such as these are increasingly communicating via WhatsApp but in this particular fieldsite, not everyone has a smartphone. The savings group wanted to ensure every member had a smartphone so they were able to communicate via WhatsApp. When this issue is discussed at a meeting, we see how group members facilitate individuals’ access to smartphones through cooperation, in a way that is aligned with the ‘smart-from-below’ approach that is characteristic of so many of the research participants in this project.