The rise of visual conversation

Previous Discovery Next Discovery

Previously, people have mainly conversed either directly using their voice, or indirectly through writing. With the rise of social media and smartphones, the visual can become an integral element of conversation.

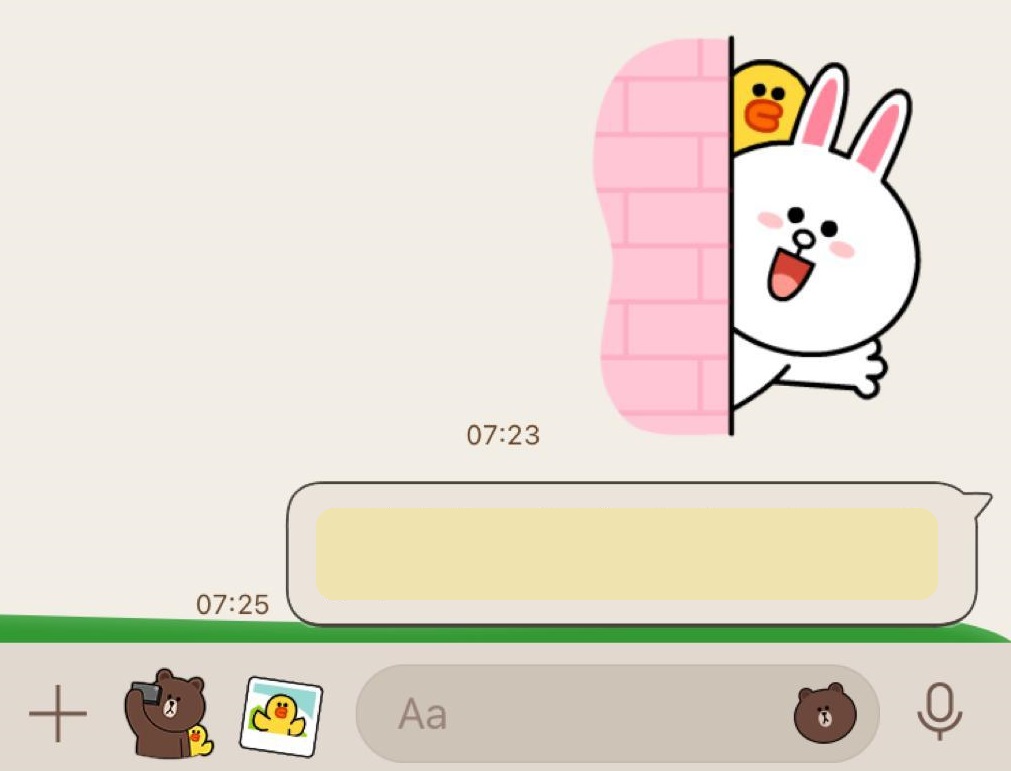

This means that there is an increasing number of conversations that are being had without necessarily needing either voice or text. In Japan, the considerable use of stickers within the dominant platform LINE (the Japanese equivalent of an app like WhatsApp) emerges from a long history of using cartoons – think of Manga culture, for example.

Older people find stickers to be a quick and easy way of expressing care and emotion. Laura’s research participants also discussed the way stickers are used to demonstrate care for others – using stickers also means one is less likely to make potentially embarrassing mistakes, such as typos. This is because, in Japan, it is important to maintain the right atmosphere in communication.

You can see some more examples of stickers like these in the photo below, which is taken from the LINE sticker store. Anpanman, one of the characters in the sticker set, is being presented as someone who can help one apologise or thank their friends.

In Shanghai, when two older people meet often the opening line might be, did you watch that health video I shared with you? This is because in China, the practice of sending short healthcare-related videos has spread rapidly over the past few years. Most retirees watch at least some short videos on their smartphones every day. These might be videos illustrating how to massage an acupuncture point near the ankle to treat sciatica and arthritis or can be videos about what diet to follow in particular situations. Ranging from 10 seconds to 2 minutes, the files are small enough to be sent as visual messages that are embedded in people’s daily conversation on WeChat (China’s most popular messaging app, though it does far more than messaging).

We found this visual element was especially important in expressing care for people who live at a distance.

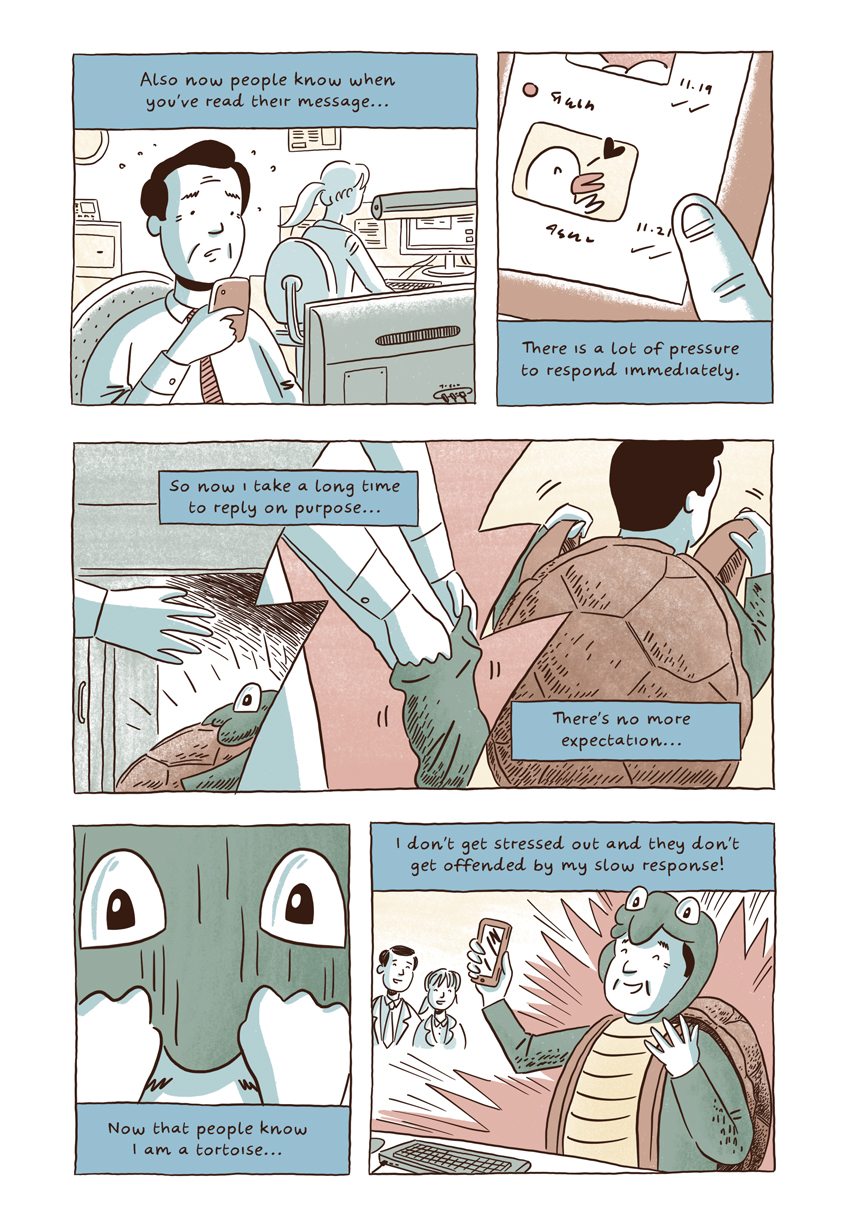

In the comic below, we meet Hiro-san, a man in his early 50s who finds the smartphone convenient, but also finds that his style of communication does not fit with what is expected of him when using the smartphone. Firstly, he likes to write long messages, just as if he was writing an email, but he finds that this style of communication does not really fit with the flowing and quick message exchanges that he has on the messaging application LINE. He also does not like the pressure to always respond immediately to messages, and the fact that people can see when you have ‘read’ a message. It exaggerates the social pressure to respond immediately in order to seem polite. In response to this, Hiro-san develops his own way to deal with these pressures by developing a ‘tortoise’ persona as he likes to call it. In the last 3 or so panels of the comic, we see Hiro-san putting on a tortoise costume over his salaryman outfit of black suit and briefcase. Based on a real research participant in the Japan fieldsite, the Hiro-san character is happy he has successfully found a way to establish his own style of messaging, characterised by a slow speed of replying and long messages.